VII:

Corruption, Immunity,

Discreation

I.

Corruption

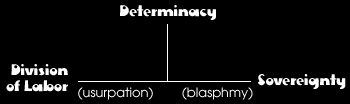

From the late middle ages forward royal absolutism was determined

by an enormously stable polarity. At one extreme kingship required

an identification or merger with the source of its authority

and the origin of its virtue. Sovereignty was secured to the

extent monarchy could lay claim to being the maker of law or

the actual presence of god. The perfection of absolutism was

a direct function of the intensity of this identification, and

its weakness a consequence of any rupture, gap or distancing.

Within the Christian tradition sovereign absolutism was condemned

to stand at a certain distance by the terror of blasphemy: the

monarch's approximation to God must always fall short of an

identification. Blasphemy was the name of a gap between divinity

and divine right. Similarly, the legal tradition inserted a

space between sovereignty and its source by virtue of an intense

reciprocity. Though kings made law, it was equally true that

kingship itself was produced by law. A law making king and a

king making law. Absolutism, constrained to a mere approximation

by blasphemy and the originality of law, nevertheless had the

power to define, reveal and specify instances of blasphemy and

to interpret the law of its creation. At the other end of this

polarity the inevitable contextualization of power produced

a political division of labor within which absolutism found

the truth of its functioning. In the exercise of its freedom

sovereignty inevitably confronted limits, crossed boundaries,

and was accused of usurpation. Thus confined by a law establishing

the specificity of its place within a system of rule, royal

absolutism had recourse to the prerogative: a mechanism of sovereign

power simultaneously subsumed within the division of labor and

perpetually threatening to transcend it. At this end of the

polarity, the tension of usurpation and the prerogative; at

the other end, the tension of blasphemy and the finality of

royal interpretations.

Since

these were two poles of a single axis of power there was a tendency

toward reciprocal implication. The proximate identification

of absolutism with the source of its virtue and authority entailed

an extended prerogative which threatened the division of labor

and generated various crises of usurpation. And in reverse:

Defense of the prerogative at the limits of its functioning

necessarily had recourse to an increasingly proximate identification

with its source, and thus confronted blasphemy. Along the axis

of power an excess at one pole required an excess at the other;

a deficiency of one implied a deficiency of the other.

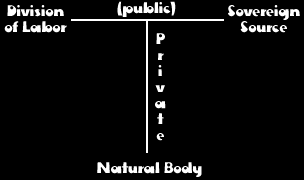

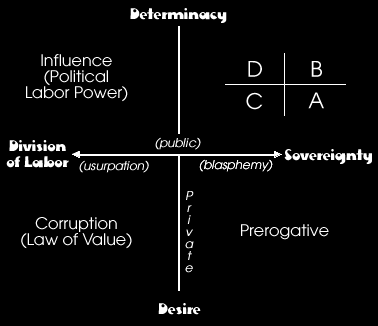

Intersecting

the axis of public power and public right constituting a legal

imperium was a radius of private power and right grounded in

a mere dominium. Along this line of difference the monarch was

neither law making king nor divine delegate but simply a finite,

temporary, completely fallible and potentially treasonous natural

person. Not the King who never dies, but the thoroughly mortal

king; not Charles II, but Charles Stuart; not the eternity (aevum)

of a divine office, but the finitude of an occupant never above

the law as its author and its sovereign source, but always below

the law and subject to it. This tangent severing and connecting

the mystical body of an absolute monarch with the natural body

occupying an office conducted a drainage as well as a contamination.

Public power could be drained off in an outward flow from the

polar axis of absolutism and be used in the service of private

desires: to enlarge the dominium at the expense of the imperium.

And in reverse: an influx of private desires contaminating the

deployment of public power for parochial, petty purposes.

The

line of difference that severed office from occupant, that drained

public power and contaminated it, also contributed to the possibility

of blasphemy. To be both God and man isr after all, a special

condition. The mystical body of Christ was a quality of being

and not an off ice, and this alone would seem sufficient to

restrain royal absolutism within an approximation. But the royal

office, immortal as suchy was also haunted by the inevitable

death of its temporal and temporary occupant whose only hope

of resurrection lay in the Corporation Sole: the diachronic

serial succession of individual monarchs each one of which was,

at her moment, the full expression of the royal species in its

infinite (aevum) multiple singularity. The death of the body

natural, or perhaps more accurately pretensions that disregard

its inevitability, supplemented the blasphemy of power with

the profanity of time. The complexity of royal absolutism was

formed along these two lines: the axis of public power, and

the line of difference with private finitude. At one pole of

the public axis lay the tension of blasphemy and its self-serving

delimitation, at the other pole the tension of usurpation and

the prerogative, and along the tangent differentiating the private

occupant from her sovereign office ran the drainage of public

power and the contamination of private whim.

This is the model of political power the modern world inherited

from Feudalism. Without regard for the relocation of the ultimate

source of virtue and authority - a shift from divine transcendence

to democratic immanence, or the multiplication and diffusion

of official power in the elaboration of bureaucratic forms,

or the "privitization" of collective power in the

form of the 19th century commercial corporation, the determination

of an office was entirely in terms of a polar public axis and

a line of differentiation severing and connecting office and

occupant: a relation with founding authority, a situation within

a division of labor, and a distinction between the indefinite

life of the office and its mortal and finite occupant. In this

sense democratic power lives in the shadow of a royal absolutism

that outlines the contours of every office while obscuring certain

of its seemingly archaic features. We see the axis of public

power connecting the poles of authority and the division of

labor, and we see the line of difference separating office and

occupant, but we tend to miss their intersection.

Since

the end of the 17th century the possibility of corruption is

a contingent relation of the distinction between private and

public in the sense that corrupt actions find their point of

origination, source of energy, and beneficial consequences in

private desires and satisfactions rather than in public motivations

and utilities. Corruption is thus posed as a problem of drainage

and contamination, and at the surface there is no reason to

quarrel with this understanding. But the difficulties arising

in the diffuse instances of supposed corruption cannot be resolved

by simply traversing the line of difference separating office

from officer. Not every usurpation, understood as a violation

of the relevant division of labor, amounts to corruption; and

alleged corruption may be avoided, elided and negated by reference

to an enlarged understanding of the connection between an office

and its founding authority.

The

President, being very anxious to have his proposals to reform

the economy accepted by the Congress, promises several of

its members who represent oil producing states that he will

veto any effort by the Congress to enact an excess profits

tax adversely affecting their constituency.

We

assume, in politics, a certain reciprocity of desire. The continuation

of an occupant in her office and the satisfaction of constituent

demands are mutually reinforcing. Both may be understood as

lying within a domain of private, particular and subjective

interests that receive sufficient political recognition to be

transformed into the currency of a public exchange. Supporting-vote

in return for vetopromise simultaneously satisfies the private

desires of officials and the equally private desires of constituents

in whose name the transaction is made. Interrogation of this

exchange for the source of its unique political character necessarily

implicates the problematic of corruption.

1.

The Veto. Above fragmentation and beyond the reach

of factions, a singular articulation of the democracy. Neither

a plebicite nor referendum but in some ways superior to both

in its access to informtion and expertise, the power of veto

encloses conflicting goals and strategies as it reconciles immediate

necessity with fundamental values and the implicit assumption

of an indefinite social continuity.

There is, to be sure, the possibility of mistake in confusing

the particular and the general good, and this is why the veto

power can never claim an absolute identification with a virtuous

authority beyond error but is constrained to approximate its

sovereign source; the impossibility of error is nothing less

than a secular blasphemy. This danger of an absolutist identification

is supplemented (certainly not caused) by the potential for

contamination flowing in along the line of difference from private

life, and most commonly makes its appearance in the form of

suspicion: the scandal of improper motivation articulating itself

upon the axis of public power as a hidden agenda. Perhaps the

history of rule should be written at the intersection of blasphemy

and scandal.

Does

this exchange of supporting-vote for veto-promise not compromise

the independence upon which a division of labor depends? What

passes, at one glance, for the mutual satisfactions of two constituencies

or the reconciliation of general and particular interests becomes,

at another, a usurpation of function arising out of the normative

certainty that no politician could resist the excess-profits-veto

promise. But a division of labor policed by usurpation cannot

allow this potential transgression to undermine the complimentarity

upon which the division depends; the wall of limitation must

also be the membrane of facilitation. Should we not, therefore,

distinguish instances of exchange from those of force and compulsion?

Quite apart from the intriguing question whether a political

division of labor can assimilate the archaic moral and modern/commercial

distinction between temptation and coercion, usurpation must

find its resolution within a framework of legitimacy along the

axis of public power according to a discourse of excess and

deficiency.

2.

The Vote. Since the 17th century the disposition of

a legislative vote finds its legitimacy within a theory of representation

intensely conflicted over the proximity/di stance connecting

and dividing the politician from her constituency. A legislative

vote may be justified by reference to the constituency as that

absolute and virtuous source of law making authority; or it

may be grounded in a recognized freedom to exercise judgment

grounded in a privileged knowledge; or it may be corrupt, the

consequence of a contamination flowing in along the line of

difference separating the office from its occupant. Unfortunately,

this simple model does not account for partial constituencies,

special interests, divergent demands, pressure groups, or the

silence of the oppressed: the multiplicities buried by democratic

totalizations. Representation is incapable of absorbing a social

multiplicity which threatens to either dissolve it by fragmentation

(how many representatives would be needed where interests are

grounded in subjectivity?), or cut it loose from sovereign authority

(an absolute multiplicity yielding an absolute independence).

Representation is be kept afloat by a haphazard, sloppy, inconsistent

and contradictory universalization of particular interests which

is other than corrupt because 'in the long run this preference

will benefit everyone,' or 'other interests will also receive

special attention thus undermining and reducing the advantage

gained' by the original privilege, and by finding the truth

of politics in that infinite circularity known as process.

In

brief outline,, these are the terms in which the legislative

vote approximates its source of sovereign authority. At the

opposite pole of the axis of power is a division of labor that

understands representation as process and participation: the

legislative vote is but one among many, and this singularity

both trivializes and displaces the potential for usurpation.

According to the great Madisonian schema, the babble of factions

self-destructs, and from the ashes of this implosion rises the

general good. There can be little danger of usurpation where

virtue reigns as an absence. Such danger as remains is the consequence

of a presidential intrusion that reduces the legislative vote

to a conduit, a mere vehicle; what is heard in the legislature

is not the voice of a constituency however elided, reduced or

transformed, but that of another office refusing to wait its

time or be confined within its space of proper functioning.

The vote and the veto are thus two aspects of the same potential

transgression.

3.

The Currency. Vote and veto may be joined with a longer

menu of possibilities. There is the promise of appointment to

high office for the legislator, a member of his family, friend,

protege, or substantial contributor to his campaign; or perhaps

an assurance of support in any reelection effort by the exercise

of suasion, influence or fund raising. There is also the possibility

of cash. What is the relevance of a currency?

Consider,

first, a specific theater of circulation within which certain

currencies are confined. Flowing along the public axis are power

relations the production and exchange of which cannot be further

abstracted. The irreducibility of these relations implies their

expression entirely within the movement and effects of bodies:

promises, appearances, statements of support, assurances, alliances

and severances, rhetorical skill, strategic or tactical skill

or the application of knowledge. In essence, the public sector

produces relations of power that circulate exclusively through

a currency of labor. This labor-power freely circulates independent

of the lines articulating the division of labor, and specifies

the relative proximity/di stance of an office from its source

of sovereign authority (i.e.r having the ear of the people,

being their voice, knowing their will, etc.). But it does not

follow that by referring to this currency as labor-power rather

than "influence", as political science would have

it, and ascribing to it a freedom of circulation, the capitalist

law of value inevitably operates along the axis of public power.

On the contrary, the value of any particular exercise of labor-power

is determined by its context, by its use across the domain of

its specific functioning - particularly in relation to the immediate

trading partner. The value of a legislative vote or a presidential

veto-promise cannot otherwise be determined. Hence the irreducibility

of this labor-power produced and exchanged within relations

of power along the public axis; perhaps a vestigial form of

the primitive 'gift'.

Consider,

second, the impact of alternative currencies. The alternative

is not really a plurality of possibilities to the extent that,

under the conditions of capitalist exchange, the law of value

reduces all options to a singular measure. The intrusive consequence

of this alternative is profound: relations of power that are

multiple, different and unique are comodified by submission

to the market law of the same. Since no other currencies can

survive this invasion there are but two reciprocal possibilities

for the axis of public power: (1) If not labor-power, then cash;

(2) If cash, then cash only.

Consider,

third, the difficulty of maintaining the irreducibility of political

labor-power as external to the capitalist law of value that

otherwise envelopes all social relations. This difficulty is

confronted at two levels. if political labor-power is exempt

from the law of value why are there not other exclusions, gaps

and special cases that reject submission to a universal currency?

And is it not exceptionally naive to suppose that relations

of power along the public axis enjoy an absolute externality

from relations of production and the consequential accumulations

of wealth.

Consider,

finally, the complex formed by four oppositions: labor-power/cash,

public/private, autonomy/participation, exchange/corruption.

The axis of public power can provide a theater within which

labor-power functions as a specific and exclusive currency only

to the extent it enjoys a certain autonomy from general market

relations. This autonomy is specified by the line of difference

severing and connecting private life, and is policed - at the

intersection - by the notion of corruption. Corruption, in turn,

is the name of a contamination along the line of difference

from the private in the form of the capitalist law of value.

The autonomy of the axis of public power is partially maintained

by this exclusion, but the exclusion is trivialized to the extent

political relations of power are inherently dependant on relations

of production, and because these relations of power necessarily

assume the universal truth of the law of value expressed in

the discourse of 'interest'.

Two

preliminary general observations seem plausable. while the general

structure of monarchy formed around the critical points of blasphemy,

usurpation and corruption survive the modern corporation - in

its state and private organizations, the capitalist revolution

introduced a shift of intensity from blasphemy and usurpation

to corruption. Blasphemy and usurpation marked the polar limits

of a political discourse centered on the prerogative. The relation

of mystical to natural body - of office to officer - was not,

strictly speaking, an additional or external limit on royal

power but was inherent in absolutist incursions either in the

direction of the sacred or toward the division of labor. After

the 17th century the focus of critical intensity is corruption:

the danger of contamination flowing along the line of difference

severing office and officer. Since the office/officer dualism

has now fully penetrated across all bureaucratic, organizations,

issues of excess/deficiency in relations of power are distributed

around the legal definition of an office. The secularization

of sovereignty and the dispersion of offices eliminates the

issue of the prerogative in its relation to absolutism and installs

in its place the problematic of law and discretion.

The

king in his body natural was fully immersed in a feudal order

that did not a sharply divide social and political relations.

To this extent the line of difference transecting the axis of

public power did not terminate in a private life: the body natural

of feudalism may not be equiparated with bourgeois privacy.

After the 17th century private life comes to be understood as

a realm of freedom - freedom from the strictures of an office

if not from the encompassing demands of moral codifications

and the dangers of deviance or degeneracy. Within this space

of freedom private individuals pursue their subjectively apprehended

and arbitrarily conceived self interest in relations of exchange

subject to the law of value. Self interest makes its appearance

along the axis of public power in two forms: as that which is

represented in political life - the irreducible signified; and

as the motivational force of representatives - the energy of

political careers infusing offices and placements generating

personal advantage and sometimes even the simulacrum of glory.

Self interest is to be otherwise excluded, but this does not

provide sufficient protection from contamination since the proper

functioning of democratic politics is determined by an essential

coincidence: maximizing the points of contact between the self

interest of the represented and that of the representative.

Hence the emergence of labor power as an exclusive currency

and the reciprocal, largely formal, and inherently contradictory

exclusion of the capitalist law of value. Politics is thus severed

from the economy by the removal of that essential linkage connecting

the pursuit of self interest to a generalized system of exchange.

One might even say that, with capitalism, the first principle

of politics is corruption

II.

Immunity.

Accountability is the name of an absurdity doomed to merely

circle about the plenitude of virtue and authority established

by the absolute identification of rulership with its sovereign

source. Accountability finds its fundamental condition of possibility

in the gap blasphemy describes between rulership and its source

of virtue and authority. But the same gap necessarily robs accountability

of a ground, a voice, an exegetical foundation. If blasphemy

keeps rulership at a distance who, in the name of accountability,

may close it? If the meaning of ruling power is given in its

privileged access to absolute sovereignty, accountability can

speak only from a position of closer approximation and, consequently,

undermines rulership by substitution. A conservative principle

of accountability appears impossible because in a singular movement

blasphemy gives it life and reduces it to silence. Justice is

not blind but mute. From the perspective of sovereignty, accountability

is treasonous when it fails and revolutionary when it succeeds.

This

is the ancestry of a series of divisions articulated upon rulership

in the service of accountability. They may be grouped as the

division of labor if it is understood that this notion encloses

the practical confrontations and ameliorations of power within

feudal or bureaucratic functioning as well as the theory of

shared sovereignty formulated as counciliarism. by the radical

branch of early civic humanism, revived and redeployed during

the Counter Reformation, and ultimately surviving in the changing

forms of the separation of powers in the English tradition from

the 17th Century forward. Though the theory of shared sovereignty

finds its point of origination at one pole of the axis of public

power, its locus of functioning is at the other - within a division

of labor formed either by the necessities of shared power within

a singularity of rulership (kingship), or within a formal structure

of multiple agencies. It is in this sense that the division

of labor solves the problem of sovereign accountability by giving

criticism a voice, by grounding it in the same sovereign source

as that which it attacks. It is no longer a question of treason,

on the one hand, or revolution, on the other, but of a middle

space wherein finality, no longer determined by the reference

of a singular office to its sovereign source, appears as a series

of resistance/escalations in the flow of power: legislation-veto-override-legal

challenge-legislative limitation on legal jurisdiction-veto-override-legal

challenge....

As

a stasis or reversal in the movement of

accountability immunities may be understood in terms of three

propositions. (1) Their point of maximum tension lies in the

confrontation with prerogative powers. (2) Immunities never

include corruption. (3) Though they may be confounded with the

division of labor itself, immunities have no normal functioning

within the division of labor but rather serve to determine the

extension or contraction of modes of accountability.

|

1. The line of difference which runs from private life, from

the natural body, intersects the axis of public power at the

prerogative - where the claims of power are most necessary,

most dramatic, and most likely to disrupt the division of labor.

The prerogative of an office may be imagined as enclosed on

three sides: by the line of difference with private life, by

the division of labor, and by its sovereign source. Because

it is fluid, labile, adaptable and readily abused the prerogative

of an office is vulnerable to attack along the line of difference

from private life - the charge of corruption. For the same reasons

it offends the division of labor - the charge of usurpation.

And its line of defense always recalls a proximity or privileged

access to its source of virtue and authority interrupted only

by the potential of blasphemy. Does a jury return a verdict

contrary to law in light of the evidence? Perhaps there is corruption.

More likely, in determining the law for itself it usurps a judicial

function. But the jury lies close to the democracy, to the sovereign

source. Having been selected to decide rationally a matter which

they would never hear were reason adequate to the task, the

jury stands grounded in the democracy speaking with the voice

of virtue and its unquestionable authority.

The question of immunity is always posed in relation to the

prerogative and thus within the framework of this triangulation.

Of course, it is no longer high office as such which justifies

absolute immunity, but the presence of a broad range of responsibilities

and duties and a wide area of discretion within the definition

of an office. Consequently, immunities may be graded, quantified

and otherwise differentiated according to a calculation of the

mix of constraint and freedom within particular agencies. Operations

which proceed in a law-like fashion, fully constrained, wholly

ministerial, can support no immunity because there is no prerogative,

and a prerogative is essential because it is that aspect which,

in the name of judgment, comprehends mistake, error and harm

as legitimate in principle. Where an exercise of prerogative

powers may be arguably unwise, ministerial operations are simply

screwed up. The scope of an immunity reflects the presence of

wisdom, and to that precise extent actualizes the functioning

of sovereignty.

2.

In the discourse of immunity, corruption makes its vigorous

appearance as a principle of difference and absolute exclusion;

and in a more tempered fashion as a principle of qualification.

As the antithesis of 'good behavior' corruption is the great

other of the prerogative, the dark face of wisdom, the inevitable

contamination of public office by private desire. By definition

no immunity comprehends behavior which has taken flight from

the axis of public power. As a principle of qualification corruption

appears as a distortion of judgment. Between wisdom and corruption

lie the potholes of bad faith, malice, recklessness: defects

of motivation which suggest but never fully uncover the invasion

of private desire.

3.

Speaking loosely, it might be said that the division of labor

as such is a creature of operationally specified reciprocal

immunities. But since it is given in the notion of a division

of labor that operations are distributed and modes of accountability

specified the negative is implicit: within its legitimate functioning

anagency may not be questioned outside the mode of accountability

that defines the division of labor. To be sure, a certain amount

of tension is generated by the need to counter extraordinary

usurpations with unusual mechanisms of accountability, but it

is doubtful whether a doctrine of

immunity has any place within the normal functioning of the

division of labor.

The

Judges, both of the supreme and inferior Courts, shall hold

their Offices during good Behaviour, and shall, at stated

Times, receive for their Services, a Compensation, which shall

not be diminished during their Continuance in Office....

and

for any Speech or Debate in either House, they [Senators and

Representatives] shall not be questioned in any other Place.

No

Money shall be drawn from the Treasury, but in Consequence

of Appropriations made by Law;

Life

Tenure as a term of office and as an immunity from discharge;

an absolute external privilege for speech as defining a deliberative

function and as stipulating an impenetrable barrier to liability.

To be sure these statements may be grasped as reciprocal figures,

ways of speaking. No one is deeply confused upon hearing that

judges and members of congress are immune in certain specific

ways, but it surely confounds ordinary understanding to speak

of unappropriated funds as immune from expenditure even though

the latter is as clear in its expression of a prerogative power

as are the two classical formulations. Since the legislative

and judicial provisions are linked in a generative or causal

manner with a political history they are said to be prophylactic

maneuvers, but so, too, the appropriation clause. Historical

linkages generally describe the struggles of accountability

with treason: Lord Coke's assertion of the privilege of artificial

reason over the natural reason of kingship; the charge of sedition

leveled at those who would critique democratic legality. These

are moments in the development of the division of labor itself,

efforts on the part of accountability to find a voice and a

grounding in sovereignty that would eliminate the interminable

oscillation between treason and revolution. The movement of

these struggles lies in the fragmentation and distribution of

prerogatives, functional privileges and points of access to

a sovereign source. To view them as immunities is to cynically

regard the division of labor as a negative formation with no

grounding save in mutual jealousy. As a matter of ordinary discourse

perhaps no great harm is done by speaking of judicial life tenure

as a piece of instrumentalism, as a strategy for isolating adjudication

from the more egregious forms of political intrusion. But something

is surely lost to understanding by the failure of this discursive

simplicity to recognize the positive linkage between the notion

of legal autonomy and an absolute exegetical finality. The infinite

regression of a law-making judge and a judge-making law is not,

after all, unrelated to the reciprocal absolutism of a king-making

law and a lawmaking king. Life tenure is a statement of the

prerogative power over adjudication within a division of labor

which presupposes a certain legal sovereignty. Perhaps this

has some bearing on the infrequent appearance of judicial life

tenure at the local level where the sovereignty of a determinate

law plays to a more skeptical audience.

We now speak of immunities in specific and limited contexts

-as, for example, an issue of absolute immunity from civil liability

in damages for injury to a private citizen. Conceding that power

is accountable within a division of labor,, significant political

energies are employed to resist or encourage multiplication

of these quite specific mechanisms. And with a vehemence which

gives the impression that the entirety of the royal prerogative

is at stake - "it is not a tort for government to govern",

particular modes of accountability suffer an exclusion, a qualified

inclusion, or are assimilated as part of an elaborate network

which, in the name of pragmatism, determines the division of

labor as a technical apparatus of power. Not, to be sure, without

considerable confusion over whether brutality, degeneracy, ignorance,

ineptitude and other illegitimate exercises of power are being

brought more fully under virtuous democratic control, or whether

the agents and agencies of the state must now govern timidly,

defensively and less. In any event, above the explosion of reports,

statements, accountings, reviews, filings, consultations, hearings

and access rights rises the question whether the classical division

of labor can comprehend an indefinite elaboration of the forms

of accountability without damaging certain central mythologies.

At issue is not a revival of classical stresses: the spectre

of legislative activism at the close of the 18th century, executive

usurpations during the new deal, or judicial stimulations after

World War II. Rather, a series of potentially disintegrative

suspicions: that the modern administrative agency is not a simple

addendum to an otherwise pristine tripartite structure; that

the exclusion from the political division of labor of the decedents

of the house of Morgan is at best an arid formalism; that when

contemporary lawsuits challenging administrative agencies abandon

any grounding in private property they not only depart from

classical forms, but also accuse traditional litigation with

its dependency on an alliance between private property and public

power.

At

a time when immunities are elaborated according to a sophisticated

calculation of governmental necessity and bureaucratic functioning,

why an interrogation in terms of this antique notion of the

prerogative? Perhaps simply to demonstrate that the utilitarian

calculation is not an indispensable mode of analysis, and that

the distribution of immunities may be determined with equal

precision through an analysis of the danger posed by private

desire, the functioning of the division of labor, and the privileged

access to sovereignty; perhaps to discover whether modern government

has a better reason for imposing unlimited liability on those

who perform routine, fully constrained, ministerial tasks than

that they do not enjoy participation in a royal majesty; or

perhaps to discover whether positive jurisprudence can account

for discretion in terms not reducible to corruption, blasphemy

and usurpation.

III.

Discretion

Discretion makes its appearance in jurisprudence along two lines

of difference. First, in its relation with law, as that which

is indeterminate and therefore Other than law; a weakness or

highly problematic gap in legality. Second, as distributed down

through a hierarchy of authority, it bears an uncertain,, ambiguous

relation to sovereign power. These two lines of difference are

co-ordinate: discretion is not a deficiency of law to the extent

it bears a secure relation with sovereign power. Consider an

exercise of suffrage, executive clemency or the veto-power.

Suffrage flourishes in the purety of choice; so absolute is

its freedom that to entertain it as an example within a discussion

of discretion appears anomolous. However stringently law may

constrain suffrage in the mechanics of its exercise, it remains

the articulation of an irreducible will. And If we are speaking

broadly, the pardon and the veto may also be counted as instances

of discretion where law merely selects proper occasions and

constructs proper objects.

There

is also a reciprocity in the functioning of these co-ordinates.

Discretion exercised in a secure relation with sovereign power

is indeterminate - and to that extent is external to a legality

that seeks to maximize determinacy. To be sure, the determinacy

of law is a central problematic of jurisprudence, but the point

is to situate this problematic in a complex that has a general

boundary describing function for legality. A sound critique

of liberal legality should assert that relative determinacy

and an intense proximity to sovereign power are inversely related,

and together they describe that which is deemed external to

law.

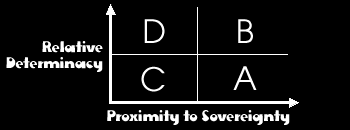

Imagine the space created by these co-ordinates of determinacy

and proximity to sovereign power as divided into quadrants.

According to this scheme suffrage, clemency and the veto should

be located in quadrant A as instances of relatively indeterminate

power bearing a proximate relation to sovereignty. With these

instances compare the decision by a relatively low level official

to grant or deny a parade permit. Given the level at which these

decisions are made within a distribution of authority the existence

of an 'untrammeled discretion' does violence to legality. The

co-ordinates of determinacy/sovereignty would specify locating

power over parade permits either within quadrant C or quadrant

D, with the movement of legality being away from the 'excess'

of discretion characteristic of quadrant C and toward the circumscription

of power in quadrant D. Generally speaking, the movement to

guide, channel or otherwise confine the exercise of discretion

by administrative agencies follows this movement from quadrant

C to Quadrant D. With few exceptions these agencies stand at

some distance from sovereign power, so the issue of discretion

within liberal legality becomes almost exclusively one of relative

determinacy. Those agents who suffer under this determinacy

and distance from sovereignty must also endure a danger of liability

for misconduct in office because they are deprived of the expansive

immunities enjoyed by officials who lay claim to the wisdom,

and therefore the relative indeterminacy, of their sovereign

proximity.

Within

this movement of determinacy the question of expertise may be

posed in a more interesting and expansive way. To the extent

expertise is asserted as a factor in opposition to the movement

of incremental determinacy (i.e., from C to D) it functions

as an alternative to proximate sovereignty. In general it might

be said that access to knowledge-power may be treated as the

functional equivalent of access to sovereign-power since the

truth value of social knowledge is grounded in the normativity

of populations, knowledge and sovereignty are two forms democratic

power assumes. More precisely, majoritarianism and normativity

are two expressions of a singular sovereignty: the former appearing

as desire, the latter as knowledge. Following this line the

expert may be located within a broad system of representation

by a movement back through knowledge and norm to sovereign population.

Two

additional examples which begin by locating both judge and jury

within quadrant C in order to describe the direction of their

respect movements. Recognition of the jury's proximate relation

with the democracy means its incremental legitimacy lies in

perfecting the process of selection - a movement toward quadrant

A. But the issue is far from one sided - compare the issue of

jury nullification with that of the special verdict in criminal

cases. On the specific question whether the jury should be told

they have the power (though not the right) to find against the

law sovereign proximity tends to lose out to legal determinacy

and the movement is toward D or B. But forcing the jury to render

special verdicts in criminal cases involves an excessive determinacy

quadrant A appears appropriate. In the case of adjudication,

the discourse of legitimacy consistently maintains that determinacy

and sovereign proximity are alternative requirements so that

a rigorous (determinate) judicial legality substitutes for a

deficient (distanced) political accountability. Legitimate adjudication

must reside in either quadrant D or A, and this accounts f or

the 'unhappy consciousness' of liberal apologists. On the one

hand, legitimacy could be secured by an incremental determinacy,

but this seems impossible even within the fictitious historical

universe of an absolute formalism. On the other hand, drawing

adjudication closer to sovereign authority endangers the particularity

of "judicial power" and thus undermines the separation

of law and politics: government under law requires a certain

distancing of adjudication from sovereignty; of reason from

will. Unable to chose between these equally disastrous alternatives

the primal instinct suggests inertia, a benign passivity that

avoids confronting sovereignty with its law at the expense of

shrinking adjudication within the division of labor.

The four quadrants specify distinct contemporary situations:

A.

The situation of discretion arising from a proximate sovereignty

and enjoying a maximal immunity.

D.

The fully determinate requirements of a distanced office the

occupant of which may be liable for error.

C.

The problem of agents and agencies currently enjoying a discretion

that, not being justified by sovereign proximity, must be

eliminated by a greater determinacy.

B.

The dilemmas of law and politics, reason and desire, fact

and value make their appearance here, a legacy of the king

making law and the law making king. In this space we dream

of the double negation that consumes alienation.

In

its indeterminacy discretion is an Other of law, and one name

of this Other is politics. Indeterminate power is, therefore,

a political power the exercise of which in a particular context

may constitute usurpation within the division of labor. The

"non-delegation" and "vagueness" doctrines

specify an inappropriate movement of indeterminate power away

from its proximate relation with sovereignty and law respectively,

a distancing that does violence to the division of labor. And

in absolutely classical fashion the charge of usurpation is

avoided by a thoroughly blasphemous claim on the part of relatively

low level (in terms of distance from sovereign source) agents

to be acting for a higher good: the virtue and authority of

justice, democracy, emergency, or the sovereign people. Discretion

becomes legitimate as against a claim of usurpation by infusing

the agent or agency with a prerogative power. The jury may thus

acquit criminal defendants against the law and the evidence

because it speaks as the voice of democracy, an actual presence

of absolute sovereignty that may never be artificially cabined

within that body of pragmatic concessions known as the division

of labor.

Like

the King, the hope never dies that law might somehow absolutely

determine the division of labor rather than be determined by

it. And so the principle of democracy as desire struggles with

the principle of law as determinate reason; the former confining

law within the specificity of the division of labor, the latter

supervising the division of labor by a determinate legality.

The release by federal judges of state prisoners held under

the authority of final judgments is a usurpation unless it can

be shown to follow from either a determinate legality or a superior

access to sovereignty necessarily generating an enlarged function

within the division of labor. Below the clamor of legality (determinacy)

and federalism (usurpation) lies the prerogative of justice

making its appearance as the federal writ of habeas corpus.

Thus the triangulated relation of sovereignty, determinate legality

and the division of labor:

The dark side of sovereign proximity, free of both determinacy

and the division of labor, is power exercised as a prerogative

of public office but thoroughly contaminated by private desire.

A white Mississippi jury is unimpressed by the eyewitness testimony

of an FBI agent and acquits Colie Leroy Wilkins of the murder

of a civil rights worker: sovereignty as corruption and the

corruption of sovereignty where usurpation is silent and blasphemy

no longer terrifies. But no one was paid for their vote; and

the jury, since Bushels Case, enjoys an immunity that

creates a space essential for its discretion. Pushing aside

double jeopardy objections in the name of the division of labor,

Wilkins may be re-tried and convicted by the fully determined

behavior of a federal jury.

The

corruption of discretion is the introduction of private desire

in the space reserved for the appearance of sovereignty. This

loathsome pit into which every exercise of prerogative office

may sink is guarded by three furies. (1) A determinate legality

permiting simple identification of the limit,, the line of difference

dividing office from occupant, public from private, the wise

judgment of sovereign virtue from the corruption of private

unreason. (2) A division of labor capable of articulating its

own principles of extension (accountability) and contraction

(immunity) according to which the mechanisms specifying instances

of usurpation are determined. (3) An exception to the law of

value that permits desire to freely circulate along the axis

of public power and across the division of labor as the irreducible

currency of service and influence.

Notes

My

argument that the division of labor solves the problem of sovereign

accountability by installing a series of resistance/escalations

in the flow of power should not be read as agreement with David

Easton's system theory. See, "A Framework for Political

Analysis" (1965, 1979).

Norm

is used here in Foucault's sense. See my essay 'Law, Norm, Rights',

in "Foucault for Lawyers", (1982).

|